Vagus Nerve: How Your Body Finds Calm or Shuts Down

- Ute Lorch

- Jun 15, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 8, 2025

What Is the Vagus Nerve?

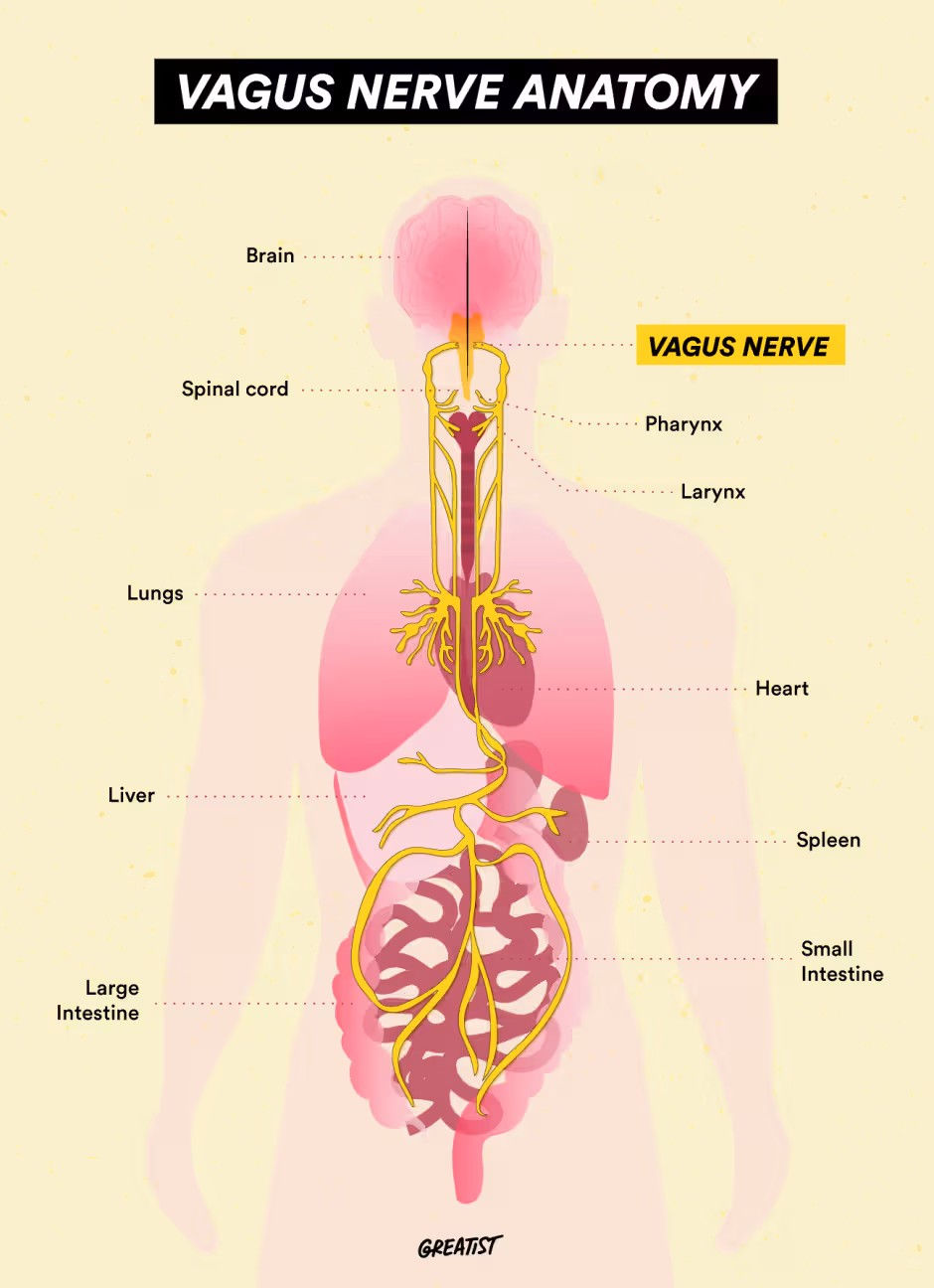

The vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) is one of the most powerful communication pathways between your brain and body. Emerging from the medulla oblongata in the brainstem, it travels down through the neck, chest, and abdomen, connecting the brain with vital organs including the heart, lungs, and digestive system.

This long, wandering nerve (its name comes from the Latin vagus, meaning “wandering”) acts as the body’s neural superhighway, transmitting information that regulates breathing, heart rate, digestion, and emotional balance. It plays a key role in the parasympathetic nervous system—the body’s “rest and digest” response—and is fundamental to how we experience safety, calm, and connection.(Porges, 2011; Thayer & Lane, 2000)

Anatomically:

Anatomically, the vagus nerve is bilateral—you have both a left and right vagus nerve. Each originates in the medulla oblongata and travels through the neck (via the carotid sheath), then branches extensively through the thoracic and abdominal cavities, innervating organs such as the heart, lungs, stomach, and intestines.(Berthoud & Neuhuber, 2000)

This structure enables bidirectional communication:

Afferent fibers (about 80%) send information from the body to the brain.

Efferent fibers carry messages from the brain to the body, influencing organ function and emotional regulation.

Functionally (based on Polyvagal Theory):

According to Dr. Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory (1995, 2011), the vagus nerve is not a single, uniform pathway but consists of two main functional branches:

1. Ventral Vagal Complex (VVC): The Social Engagement System

Originating in the nucleus ambiguus of the brainstem, the ventral vagal pathway supports facial expression, vocal tone, social engagement, and calm states. It promotes safety and connection, regulating heart rate and respiration during social interaction.(Porges, 2007) Signs of a Healthy Ventral Vagus Tone:

Calm, steady breathing

Easy eye contact and social connection

Stable heart rate variability (HRV)

Summary:

The ventral part of the vagus nerve is on both sides of the body.

It's named "ventral" because of its origin in the ventral brainstem (nucleus ambiguus), not because it's only on the front or a particular side of the body.

The ventral part of the vagus nerve, also known as the ventral vagal complex, refers more to its functional division than a strict anatomical location.

2. Dorsal Vagal Complex (DVC): The Shutdown Response

Originating in the dorsal motor nucleus, this older evolutionary branch supports immobilisation, energy conservation, and digestive regulation. When activated under threat, it can lead to freeze or shutdown responses.(Porges, 2011; Schauer & Elbert, 2010)

Signs of Dorsal Dominance:

Emotional numbness or withdrawal

Digestive sluggishness

Fatigue or “brain fog”

Ventral vs. Dorsal Vagus Nerve: So, what's the Difference?

The Ventral Vagus Nerve: Social, Calm, and Engaged

This branch supports social connection, calm breathing, vocalisation, and heart regulation. It's your body's "safe mode."

Signs of a Healthy Ventral Vagus:

Calm, steady breath

Social interaction feels natural

Heart rate is stable

The Dorsal Vagus Nerve: Freeze and Shutdown

This older branch controls deep organ regulation and can trigger shutdown during trauma, fear, or overwhelm.

Signs of Dorsal Dominance:

Emotional numbness or withdrawal

Digestive sluggishness

Fatigue or brain fog

The Autonomic Ladder: Tracking Nervous System States

Polyvagal Theory describes the nervous system as a hierarchical ladder with three main states:

🟢 Ventral Vagal (Safe & Social) – Calm, engaged, connected

🟡 Sympathetic (Fight or Flight) – Activated, mobilised for action

🔴 Dorsal Vagal (Freeze/Shutdown) – Collapsed, withdrawn, disconnected

Understanding where you are on this ladder helps you respond to stress with awareness, not self-blame. Your nervous system isn’t broken—it’s adaptive, shifting automatically to keep you safe based on perceived cues of danger or safety.(Dana, 2018)

Supporting a Healthy Vagus Nerve

The vagus nerve can be toned and strengthened through lifestyle and therapeutic practices that engage the parasympathetic system and promote a sense of safety.

Evidence-based methods include:

Slow, diaphragmatic breathing – Stimulates vagal afferents and increases HRV (Laborde et al., 2017)

Humming, chanting, or singing – Vibrations stimulate the vagus via the vocal cords (Porges, 2007)

Cold exposure – Triggers vagal activation and improves stress resilience (Breit et al., 2018)

Safe social connection – Strengthens the ventral vagal network (Cozolino, 2014)

Trauma-informed therapy and mindfulness – Promote neuroplasticity and re-regulation of vagal tone (Davidson & McEwen, 2012)

Technique to tone the vagus nerve

The Adaptive Nervous System

Your nervous system is designed to adapt. Through neuroplasticity, the brain rewires based on repeated experiences, thoughts, and emotions. This means that vagal tone—and therefore emotional regulation—can improve with practice.When you understand how your vagus nerve works, you gain the ability to guide your body back to safety, calm, and connection.

References

Berthoud, H. R., & Neuhuber, W. L. (2000). Functional and chemical anatomy of the afferent vagal system. Autonomic Neuroscience, 85(1–3), 1–17.

Breit, S., Kupferberg, A., Rogler, G., & Hasler, G. (2018). Vagus nerve as modulator of the brain–gut axis in psychiatric and inflammatory disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 44.

Cozolino, L. (2014). The Neuroscience of Human Relationships. W.W. Norton & Co.

Dana, D. (2018). The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy. Norton.

Davidson, R. J., & McEwen, B. S. (2012). Social influences on neuroplasticity: Stress and interventions to promote wellbeing. Nature Neuroscience, 15(5), 689–695.

Laborde, S., Mosley, E., & Thayer, J. F. (2017). Heart rate variability and cardiac vagal tone in psychophysiological research. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 213.

Porges, S. W. (1995, 2007, 2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W.W. Norton.

Schauer, M., & Elbert, T. (2010). Dissociation following traumatic stress. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 218(2), 109–127.

Thayer, J. F., & Lane, R. D. (2000). A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 61(3), 201–216.

Comments